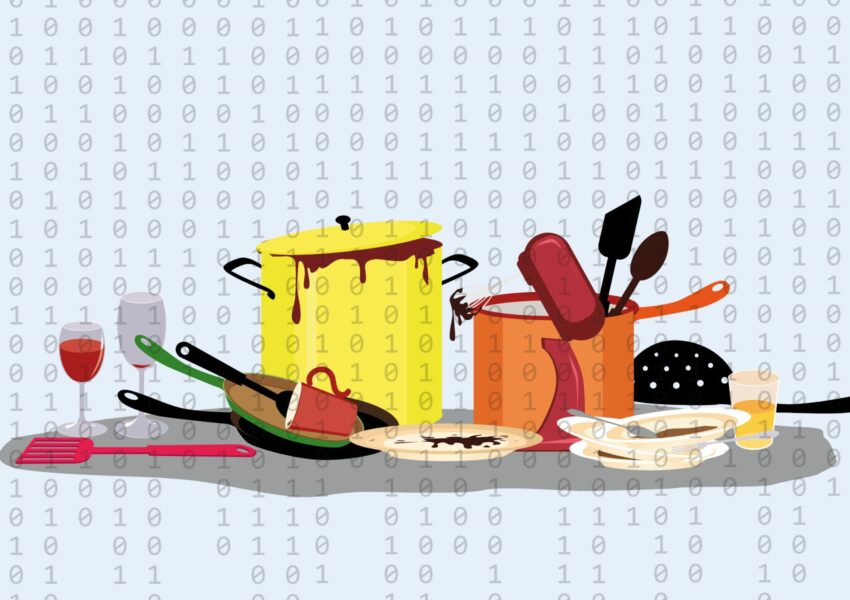

If you have ever lived with flatmates, you will know the pain of unwashed pots and pans piling up in the sink. At first it does not seem like a big deal. But leave it a day or two and suddenly the stack is taller, the food is more stubbornly glued on, and you are out of clean pans to cook with. That is what engineers mean when they talk about technical debt in software.

It is the invisible, slow-growing problem that can eventually grind projects to a halt. Dave Evans, Senior Software Engineer at Thalamos, calls it “the invisible killer of software projects”. Like carbon monoxide or cholesterol, you cannot see it directly, but if you ignore it the consequences can be severe.

So, what exactly is it, how does it happen, and why should non-engineers care? Evans unpacks his “invisible killer” description below.

The gap between today and best practice

Every industry has best practices, agreed ways of doing things properly. In software, these evolve fast as tools improve and understanding deepens. That is where debt creeps in.

Think of technical debt as the gap between what your software looks like today, and what it should look like if it conformed to current best practice. Closing that gap takes work. And, just like financial debt, it comes with interest: the longer you leave it, the harder it is to pay off.

For example, the moment your team adopts a new coding standard or testing approach, every bit of code that does not meet that standard becomes a debt to address.

It is not bugs or features

It helps to understand what technical debt is not.

- Bugs are mistakes, like dropping a ten-pound note from your pocket. It is gone, but you do not owe anyone interest on it

- Features are like extensions on your house. They cost money or developer time to add, but that is a conscious choice

- Technical debt is the backlog of “should-do” improvements that have been postponed. They slow everything down, even if you do not notice it straight away

Why it matters

Debt weighs projects down. More debt means work gets harder, features take longer, and quality suffers. The tricky part is that it is mostly invisible. Even engineers working closely on the code often cannot tell you exactly how much debt exists, or how much there should be.

When managers set aggressive goals with fixed timelines, engineering teams often cope by quietly deferring best-practice work. On the surface things look great and features ship fast. Underneath, debt is piling up. Weeks or months later, progress slows to a crawl, or the system collapses under its own weight.

We have all seen examples: clunky old software that feels bloated and frustrating to use. Often, the reason is simple. Teams did not keep on top of their technical debt.

Everyday metaphors

Here are some vivid comparisons to make the point:

- Flatmate dishes: leave them and they pile up, getting harder to clean, until you cannot cook at all

- Loans and mortgages: like money, some debt is manageable, some is worrying, and some is catastrophic. The trick is knowing what level you are at

- Death by a thousand paper cuts: one or two ignored tasks are not fatal, but many small ones can tip a system over

These stories show that debt is not always bad. Sometimes it is a strategic choice. But like financial borrowing, it must be paid back.

Measuring the unmeasurable

Unlike money, there is no monthly statement for technical debt. Engineers instead track simple, countable things:

How many outdated third-party packages are still in use

The percentage of code covered by automated tests

The number of small “lint” issues, such as discouraged but technically correct ways of writing code

These are not perfect measures, but they show whether debt is going up, going down, or holding steady. The goal is not to hit zero debt, which is unrealistic, but to keep it at a healthy, manageable level.

Who should care?

Technical debt is not just an engineering concern. Anyone who influences priorities, from product managers to executives, should pay attention. That is because debt directly affects speed, quality, and cost.

If decision-makers only look at the surface, such as fast feature delivery, and ignore the underlying debt, they are setting the team up for pain later. Sometimes the best business decision is not to add another feature, but to give engineers time to pay down debt.

The cost of neglect

When teams ignore technical debt for too long, the results can be severe:

- Legacy systems become unmaintainable, like houses collapsing under the weight of an unpaid mortgage

- Old codebases can no longer run on modern computers or integrate with modern tools

- Productivity collapses as developers spend more time fighting the system than building new things

At that point, the only option may be to declare bankruptcy, scrapping the old system and rewriting it from scratch. That is hugely expensive and disruptive.

Managing it well

Healthy organisations treat debt like a mortgage: something you pay off gradually, every sprint or development cycle. A bit of time goes to features, a bit to bug fixes, and a bit to paying down debt.

The balance is not fixed. Sometimes it makes sense to deliberately take on more debt, for a big launch for example. At other times the focus should shift to paying it down. The key is visibility: tracking the numbers, sharing them, and adjusting priorities accordingly.

The bottom line

Technical debt is unavoidable. Every piece of software has some. The danger is not in taking it on, but in pretending it is not there.

Think of it like cholesterol: you will not feel the damage day to day, but if you never measure it, one day you may find yourself in real trouble.

By recognising debt, measuring it, and steadily paying it down, organisations can avoid collapse, keep their software healthy, and continue to deliver value.

Or, to return to the kitchen sink: wash your pans as you go and you will always be able to cook dinner.