Not a portrait on the wall: Sheila Stenson on visibility, rigour and KMMHs next chapter

27 January 2026

Kent and Medway is not a place where leadership can be done at arm’s length. With services spread across 30 sites and around 60 buildings, the job has a way of testing whether an organisation’s ambitions can survive contact with day-to-day reality.

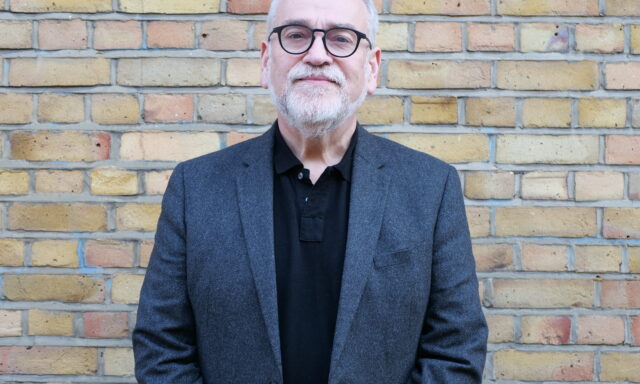

For Sheila Stenson, Chief Executive of Kent and Medway Mental Health NHS Trust (KMMH), that geography has reinforced a leadership style grounded in visibility, consistency and a deliberate effort to stay close to staff experience.

“I never wanted to be a CEO that’s a picture on the wall,” she explained. “I want to be someone that we’ve met, we can relate to, and who understands the issues and concerns we might have because we’ve talked to her about them personally.”

That instinct runs through the way she talks about performance, finance, culture, digital change and the place of lived experience in shaping services. It is also rooted in earlier moments in her career when organisational change was not abstract, but immediate and disruptive.

Learning leadership through disruption

Asked what experiences have shaped how she leads today, Stenson went straight to challenges. She pointed to her time at South London Healthcare NHS Trust, formed through the merger of Queen Mary’s Sidcup, Bromley Healthcare and Queen Elizabeth Hospital Woolwich. She lived through the merger and then, a few years later, the dissolution of the organisation. That sequence, she explained, was formative precisely because it demanded two very different leadership mindsets in a short space of time.

Those lessons now translate into a set of anchors she returns to repeatedly. “For me it’s always thinking about the people,” she said. “The patients that we’re looking after on a daily basis.” The second anchor is staff. She described the mental health sector as being fundamentally reliant on people in a way that differs from acute care. “For us in the mental health sector it’s so much about our staff and people,” she added. “We have to be thinking about the wellbeing of our people, developing them.”

“Finance can’t sit in a bubble. It has to be part of clinical and operational decision-making.”

Connection at scale

Being visible across a large and dispersed Trust takes more than good intentions. One of her most established routines is a monthly open session called Speak to Sheila, where any member of staff from the 4,000-strong workforce is invited to ask whatever they want. Alongside that, she sends a regular written update to staff and uses structured manager communications to help maintain a clear organisational narrative.

Stenson is candid about the financial challenge she inherited when she joined KMMH in late 2017 as Chief Financial Officer (CFO). She described walking into an organisation that believed it was just alright financially, only to discover quickly that it was carrying a substantial underlying deficit, coming close to £11-12m a year.

Coming from the acute sector, she brought an expectation of service line reporting and a sharper link between expenditure and income. In mental health, she found a different norm. “We did divorce the two,” she said, describing how the Trust tended to focus on expenditure budgets while income sat over to one side.

Introducing service line reporting gave KMMH a way to see the problem more clearly. “Quite quickly we could see within the first three months that actually half of our deficit was being driven by the forensic services,” she said. From there, the work became both internal and external: benchmarking across sites and engaging NHS England and peer providers to compare cost bases and income arrangements.

The wider point, for Stenson, is that finance cannot sit in a bubble. It has to be integrated with operational and clinical decision making.

Data, improvement and metrics

On data, Stenson was direct about both the opportunity and the gap. KMMH has introduced an improvement methodology that links overall direction to specific objectives in priority areas. In dementia, where the Trust has managed to halve waiting times, it has worked well because it forced a tighter grip on data and created more granular visibility across the patch.

However, she does not believe this level of rigour is yet consistent across all services. She also made a wider point about national focus. In acute care, a long history of targets has embedded a discipline around waiting times and pathways. Mental health does not always have the same shared structure. “I really wish we could benefit from having maybe six metrics, for example, which we’re all monitoring and we’re all measuring in the same way,” she said.

Digital change, for Stenson, is inseparable from workforce experience. On artificial intelligence, she sees immediate relevance in tools that reduce time spent on documentation. She described the workload involved in crisis assessments, where staff may spend as long typing up notes as they do carrying out the assessment itself. “Ambient voice has to be the way to go for us going forward,” she urged.

The Trust’s digital champion network, around 80 strong, acts as a bridge between strategy and daily practice. The purpose is twofold: to test whether tools will work in real settings, and to help KMMH prioritise. “There’s so much available around digital at the moment,” she said. “We could be doing hundreds of things but actually we want to be doing two or three things that are going to really make a difference.”

“We could be doing hundreds of digital things, but we want to do two or three that genuinely make a difference.”

Culture, safety and allyship

When she became Chief Executive, Stenson said it was clear from staff feedback that wellbeing, equality, diversity and inclusion required greater focus, including concerns about racial abuse and whether the organisation was taking it seriously enough.

She described bringing in independent support to gather feedback, alongside a major staff survey. That work informed a plan that included a practical emphasis on violence and aggression, particularly in ward settings. The Trust has since seen meaningful reductions in some areas. She was also clear that this is not quick work. “This is linked to culture,” she said. “It takes a while sometimes to shift that culture.”

KMMH has established a small co-production team, employing people with lived experience and aligning them to directorates, with the intention of embedding lived experience input into everyday service shaping rather than treating it as occasional consultation. KMMH also has around 50 peer support workers across services, and Stenson described an ambition to connect peer support and co production more effectively.

What 2026 brings

Looking ahead, Stenson expects 2026 to be shaped by several major themes: responding to CQC feedback through the Trust’s quality plan, adapting to an evolving commissioning landscape, and preparing for the transfer of children and young people’s mental health services into KMMH.

When asked what would feel like a job well done in three to five years, she returned to outcomes, experience and access. She wants to be able to show the impact of services more clearly, and to see improvements in patient experience. She also wants people to be able to access services more quickly, and she sees digital progress as a necessary enabler of that, particularly if it reduces admin burden and gives staff more time for care.

This article is part of a wider interview series with Mental Health Trust and ICS executive board members. Others of interest include:

- Getting the culture right so we can flourish: Sean Duggan on Sussex Partnership’s next chapter

- Empower, don’t control: how Feroz Patel is reshaping finance at Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- Leading through uncertainty: Arun Chidambaram on change, culture and the future of mental health care

- Turning policy into practice: Viral Kantaria on leading integration across Coventry & Warwickshire