Our impact

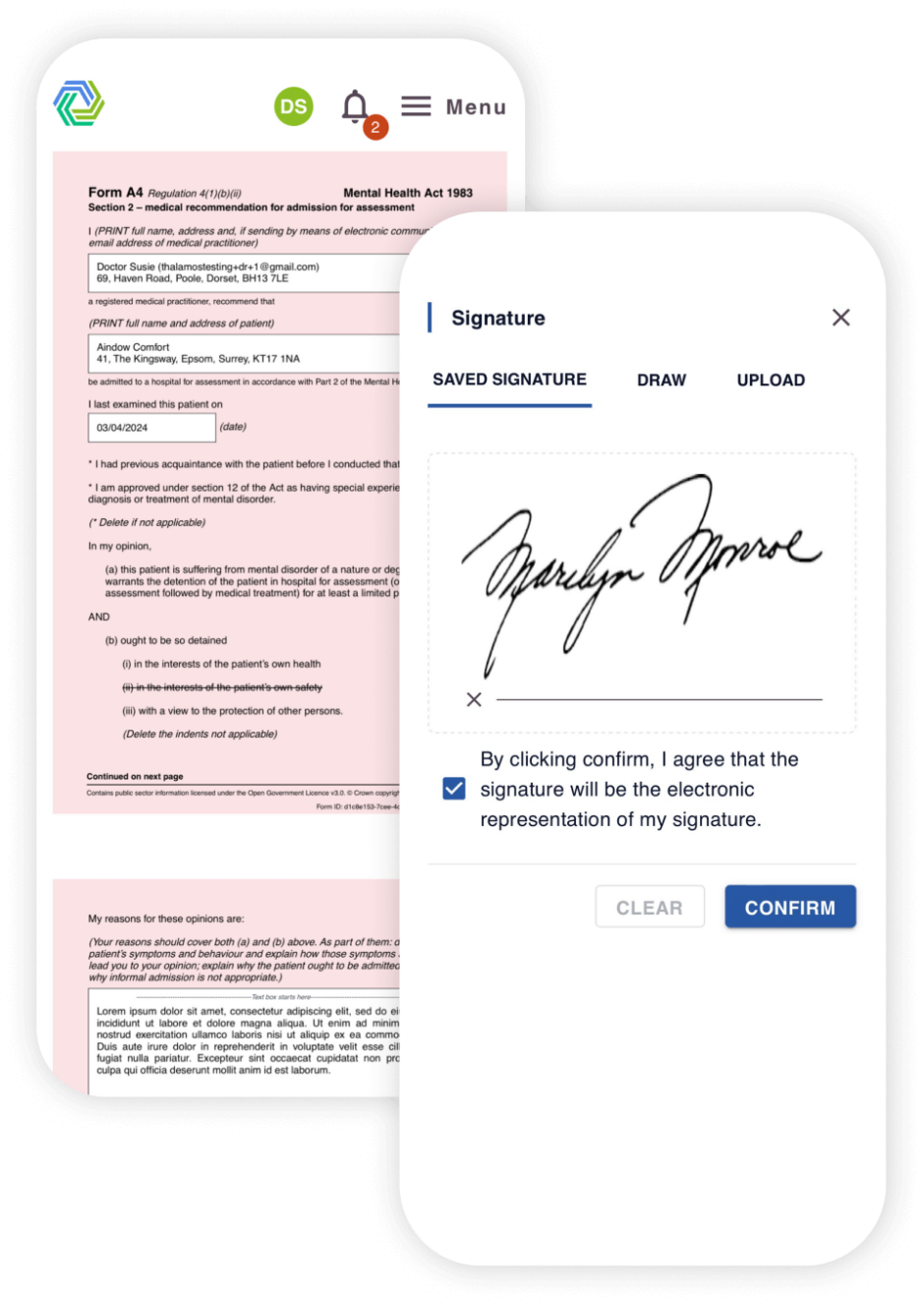

Our solutions improve the efficiency, accuracy, and overall patient care.

Thalamos reduces inefficiencies, improves patient care, and supports better health outcomes.

We believe that there should be no distinction or disparity between emergency physical and mental health care as exists currently.

Our solutions improve the efficiency, accuracy, and overall patient care.

Thalamos has helped reduce access to treatment times from 7 days to 15 hours.

Patients can be discharged 1-3 days sooner by trusts using Thalamos.

At one site using paper, there was an estimated 25% error rate, this error rate has been dramatically reduced to 1.6% since using Thalamos.

When a close friend of Arden’s was sectioned under the Mental Health Act, there was disbelief that an emergency care pathway was managed by moving around paper forms.

Disbelief turned to shock when it became apparent that access to treatment would be delayed whilst they waited for the set of forms to be circulated manually and finally signed off.

Thinking there must be a quicker and more efficient way of accessing treatment during a mental health crisis, Arden and Ross founded Thalamos to digitise the entire care pathway.

Existing customers

If you are looking for support while using Thalamos, please email support@thalamos.co.uk or call 0203 886 0385.

If you work for, or with: